A Founder's Guide: Thoughts on Moats

Written April, 2021. Published Aug, 2021.

Objective

This document acts as a journal entry of sorts, that describes Amol’s miscellaneous thoughts on moats and how startups can build and defend them. It also acts as a reference for the strategies that we can use to build moats that will be relevant for our company.

On Moats

Companies live and die based on their ability to carve out unique niches for themselves. The starting goal of every company is to become a monopoly in some small part of a massive market. Once the company is indispensable in one small area, the company is free to expand while always maintaining a foothold. The initial monopoly point can be incredibly small -- maybe the market is only 100 people -- but as long as the company is a monopoly in that space, it can thrive.

Why a monopoly? Because a monopoly means profit positivity. If you are the only person providing value in some key part of some tool chain, you can upcharge to generate profit that can then be reinvested to grow the business. That can mean expanding to new markets or shoring up the monopoly you have; either way, it’s good. See: competition is for losers.

A monopoly is defined by moats -- namely, the parts of your product or business model that prevent others from stealing your thunder. I tend to think of moats as ‘reasons people will use my product, even if someone else copies everything about it that is public’. Every startup needs to think at least a bit about what their moats are, how they can be strengthened, and how to build new ones. Once your moats are in place, you have a defensible position from which you can expand outward to exert influence and grow revenue.

Types of Moats

In the modern tech world, there are roughly four kinds of moats:

- Technological improvements.

- Data storage.

- Network effects.

- Infrastructure moats.

I don't love the name 'moat'. Was 'competitive advantage' too many syllables?

Technological Improvement

Technological improvement moats are a catch-all that describe any kind of product or design improvement on some existing technology or problem space. Many startups start with tech moats, including virtually all startups coming out of academia. In many cases, this is fairly intuitive -- tech moats are directly tied to product, and relate closely to what founders believe is wrong with the world. The things that make you better than alternatives as a product are also the things that define your moat.

The depth of the tech moat is therefore a direct function of how much better you are than alternatives. Alternatives doesn’t just have to be other comparable companies -- your tech moat depends on things that are substitutes as well.

Unfortunately, the tech moat is the weakest moat on the list. Unlike every other moat, a tech moat weakens with time and has inverse value with investment. In order to build a tech moat, a company must evaluate several possible products before deploying the one that actually works; competitors can copy the one that works directly, saving them on time and money. Further, anything that is public-facing loses any stealth protections, resulting in copycats. It is possible to maintain a tech moat by hiding the secret sauce, but the nature of CS is such that most things will become open (or obsolete) sooner rather than later.

This is why at the start of a company, an effective tech moat must be at least 10x better than anything else on the market. A 10x improvement gives the company enough lead time to establish itself, after which it can develop other, more long lasting moats.

Ford is an excellent example of a tech moat. Ford’s method for manufacturing cars was so much better than everyone else that they essentially monopolized the automotive industry in the US for decades. Google is another, more recent example -- PageRank was so much better than whatever Yahoo was doing, that Google became the internet default within a year of founding. In both cases, the companies were able to utilize the initial boost generated by their tech moat to build stronger moats in other places.

If you search 'moat' on Google, almost all of the pictures are from tech articles about Sillicon Valley companies. But they still use pictures of actual moats.

Data Storage

As the name would suggest, data storage moats are those that naturally arise out of a company storing data. Data storage moats can be broken down into storage-as-a-product, storage-as-customization, and storage-as-fuel. These all function in different ways, but all depend on data storage in some form.

Storage as a Product

An object at rest stays at rest. When users upload data to a storage service, that data stays on that service. As a result, any service that offers personal data storage can craft a moat around the stickiness of user behavior when it comes to moving data between locations.

Data stickiness cuts both ways, however -- users are unlikely to upload data to a platform unless there is a compelling reason to do so. As a result, the 'default' storage service has a huge advantage. This is why Google Photos automatically uploads from a user’s phone; the user never has to think about moving the data, it just happens.

The storage product moat obviously scales depending on the amount of data a platform is storing. If a platform only has a few bits of information about a user, like name and address...well, that's a pretty weak moat. But if the platform has terabytes and terabytes of a user’s data, that user is basically never going to leave.

Dropbox is an excellent example of a storage product moat. Dropbox offers only 2GB of free space and in its modern incarnations is significantly worse in almost every way compared to Google Drive. However, I and many others still use Dropbox, because when it first came out it was the only game in town, and all of the data that I ever put on Dropbox is still there.

Taken from Dataedo

Storage as Customization

Data storage doesn't have to come from user upload. Every time users interact with a platform, there is an opportunity to store data. Many of these interactions can be used for customization, which in turn makes the platform more attractive to the end user and creates a compelling moat on its own.

Whenever a user manipulates something on a platform, they feel a piece of ownership over the creation -- whether that be a slightly different ordering, or even just a name change. Some platforms allow intense customization, which in turn makes users feel intensely attached to the platform. Platforms that require specific skills to use have additional moat-qualities due to the nature of sunk cost.

Of course, this all cuts both ways too. If a platform is hard to use without customization, it will be difficult to attract new users; conversely, the harder it is to use, the more likely already-converted users will be users for life.

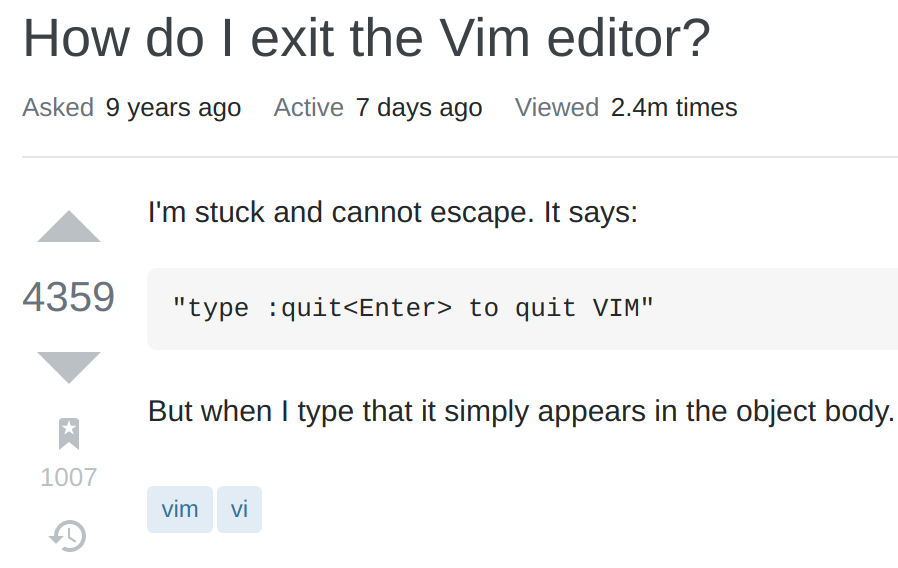

There are dozens of great examples of this moat in action, but my favorite is Vim. Vim is objectively a terrible text editor, but I can customize it to do exactly what I need, which means I will never use anything else. Spotify is another compelling example of this moat. Even though Spotify generates value by streaming music, it retains users against copy-cats due to the stickiness of Spotify playlists. Once a user builds a playlist on Spotify, they won’t ever leave. Tumblr is another good example where the high levels of customization that people put into their blogs results in long term stickiness.

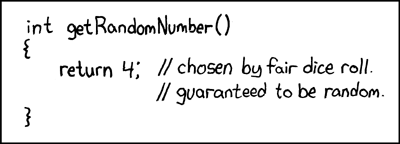

This will forever be my favorite stackoverflow question.

Storage as Fuel

Big data can be seen as a moat in itself -- basically, storing user interactions as a means of generating datasets for training recommendation engines and the like. This is the weakest data storage moat, but it is surprisingly popular right now due to the hype around big tech and ML. While it is true that companies like Google are able to turn massive amounts of data into insights about user behavior, I think in practice this is basically a waste of time for any startup.

There are several companies that collect large amounts of data to explicitly sell to advertisers. These companies suck, and also immediately lose their moat the moment they sell the data, so it’s a wash.

This is my big data generator. I process it using machine learning.

Network Effects

Network effect moats occur when a platform becomes better as more people use it. Because users gain additional benefits from being around other users on the platform, other companies need to build a product that is so much better that the network effects don’t matter. I think of these moats as ‘1 + 1 = 3’. For the same reason, network effect moats are hard to build, especially when competing against someone else that is also trying to create (or has) network effects in the same space. Products that depend on network effects are often terrible when they start.

There are two kinds of network effects: those with homogeneous users, and those with heterogeneous users.

Network effects.

Homogeneous Networks

In a homogeneous network, every user is the same type of user. Each additional user that is added to the network is a unique net positive that drives growth for every additional user afterwards.

The canonical example of a homogeneous network moat is Facebook. Facebook benefits from each additional person who joins the social network. Even though Facebook objectively makes a terrible product, everyone has to be on facebook because everyone else is on Facebook. At this point, there is no possible product development that could possibly be strong enough to unseat Facebook; better products existed (G+, imo) but were insufficient to overcome the massive benefit Facebook gets from having everyone already on the platform. The only way to beat Facebook is to target new generations of users. Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok actually tried this. Insta got bought, while Snap has to watch as its features get cannibalized by Insta. TikTok is alive and well, though Facebook is trying its hardest to cannibalize them too.

More generally, any social network has these kinds of network effects, including Twitter, LinkedIn, and Tinder.

Heterogeneous Networks

In a heterogeneous network, you have more than one kind of user. Generally, in these networks, the addition of a user of type A provides more value to users of type B, and vice versa.

The canonical example of heterogeneous network moats is any kind of marketplace. Markets benefit from virtuous cycles in consumers and producers -- the more consumers there are, the more producers want to be there; and the more variety (and competition between) producers, the more consumers will show up. Netflix is an excellent example of a company that has managed to turn their heterogeneous network moat into a massive industry success (see Ben Thompson for more).

Infrastructure

The last moat worth mentioning is the infrastructure moat -- moats generated by accrued capital, assets, or relationships. In some ways, these are the OG moats. Manufacturers, railroads, telecommunications, and more are basically all protected by infrastructure moats. In the modern era, infrastructure moats can include patents and licenses. For example, Spotify and Netflix both have impressive infrastructure moats that come out of the licensing agreements they have with music/movie distributors respectively.

Amazon has perhaps the largest modern infrastructure moat. Their logistics operations (including physical holdings in the form of real estate, warehouses, trucks, employees, and more) are absolutely incredible. This moat has propelled them to being a global juggernaut that is trying to eat the entire concept of commerce.

In our next talk, we'll discuss common ways to get around moats, like trebuchets.