A Founder's Guide: Communication at Google

Written Jan, 2022. Published Feb, 2022.

Anyone who says they're great at communicating but people are bad at listening is confused about how communication works.

Communication is what happens when person A takes information that lives in their mind, and successfully transfers it to person B. Organizations (including companies) exist because multiple people can work more efficiently on larger projects than an individual person. Naturally, communication is the lifeblood of an organization. An organization without communication isn't even an organization, it's just a bunch of random people doing things separately from each other.

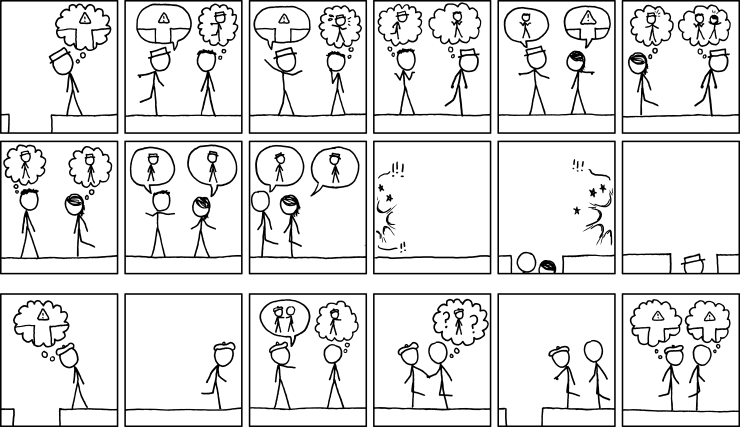

Unfortunately, it turns out communication is a fairly difficult task! Everyone comes to the table with different expectations, lived experiences, biases, and priors. This results in lost signal, as each person interprets the same input information through successive layers of personalized lenses and filters. I really liked this thread by Dan Luu that encapsulates the problem in an organizational setting.

To get around this, we've invented all sorts of ways of communicating. In person face-to-face talking is one small, tiny part of the communication landscape; the vast majority is made up of writing and figures (including IM, email, documentation, figures, READMEs, and even code); and the rest is rounded out by video streaming, audio recordings, presentations, interpretive dance, and puppetry. Each of these modalities is best suited for a specific kind of information transfer, almost all of them benefit from special tooling and shared cultural standards, and all of them have their own set of difficulties. Sometimes the tooling sucks, sometimes tone or context or more is lost, sometimes people who are great at presentations are bad at writing emails or handling puppets. With long lasting communication, like a how-to guide, there is a ton of added complexity around just making sure that the right people even know the information is out there. Honestly, it's amazing we get anything done at all.

I thought communication at Google was really good — from the moment I joined the company, I almost never felt confused about what to do, who to talk to, what the focus of my team/org/company was. The main reason for this, without a doubt, is that Google is filled with helpful, talented people. I loved everyone I worked with and almost all of them were more than willing to answer random questions and teach me about [programming, operating inside of Google, dealing with relationships]. But it's hard to get good people, and I don't want to focus too much on hiring practices here. Instead, I want to look at two other key aspects of Google's internal communication strategy: spectacular tooling and really strong cultural norms.

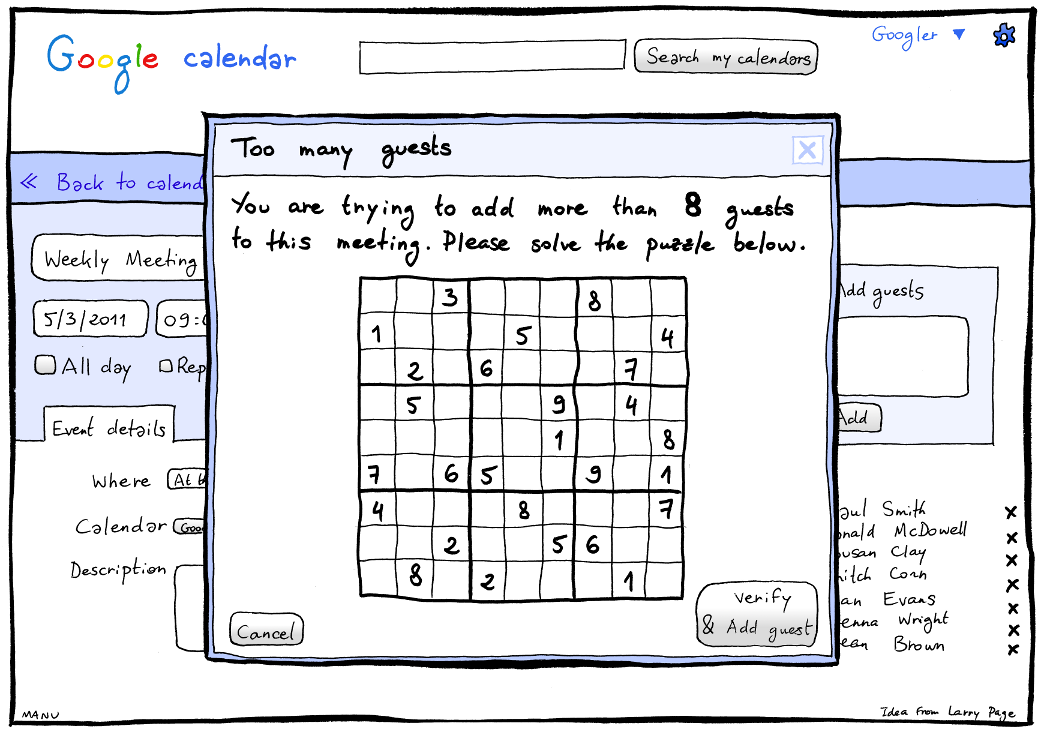

Like I said above, communication comes in many forms. Google has tools for all of them. Some of these you might know from public use (gmail, docs, sheets, slides, meets, calendar). Some of these you may have heard of, like critique for code review and the internal okr trackers. And some are more unique to google, like gdoc, a markdown-esque language that was used for automatic website generation to treat 'documentation as code', or YAQS, an internal stack overflow. Independently, I think these tools were mostly adequate, with the exception of critique which was really quite good. But they shone when they were put together, and they were unstoppable when combined with Google Groups and Google's internal search infrastructure.

Every single one of these tools was built to interoperate with all of the others. Some did this explicitly — for example, automatically including a Meets link with every calendar event — but most used email as a lingua franca. Share a doc? You get an email that could be used to reply without ever leaving the inbox. Comments on a design review? All editable from gmail. Code review coming in? Email. Calendar event? Email. Sending an email? Email. Almost every single thing that you could do could be accessed in your inbox.

But your inbox didn't have to be your inbox. Google Groups were a ubiquitous way to create group inboxes that functioned identically to mailing lists. You could make a Group for anything, though many groups were automatically created as a reflection of the company hierarchy. (The moment I joined Google, I was automatically put into individual Groups for every manager in my chain, up to Sundar.) If everything can communicate via email, and you can set up group inboxes for arbitrarily granular groups of people, you can build automated fine grained communication channels. Suddenly, you can use any tool you want to communicate — really, whatever you are most comfortable with to get your point across — and you can be sure that it will get to the right people.

And Moma, Google's internal search engine, filled in the gaps for everything else. Moma automatically indexed everything you had access to, including calendar events, people in the directory, public group lists, everything in Drive, and, yes, your email(s). I briefly mentioned in Corkscrew Development that simply letting people know your work exists can be a huge multiplier on how impactful it is. A search indexer like Moma is a natural end goal of that line of reasoning, because it can connect all of your company's information to everyone, present and future, who might need it most.

On my current team, we mostly use Slack, and a lot of really important communication gets totally buried and is impossible to find. Things like Q&A with the 'team expert', posting about/debugging errors, design discussions, etc. I think the real beauty of the system at Google is that it successfully captured all of the knowledge transfer that happened in casual email threads, and stored/indexed them so that anyone can find them later.

Of course, the technology only goes so far. Google pairs all of this technical infrastructure with strong cultural norms. Folks do use IM (Google Chat, which is also indexed by Moma as an email!) but there is a real commitment to using email and Groups. Similarly, where possible, people try to share things globally, a natural consequence of deeply entrenched transparency. Virtually everything has a go/link, which makes hopping around from document to document easy and memorable. And of course, Memegen participation and consumption was a ubiquitous part of Google's company-wide communication, allowing far-flung employees to keep a near-instantaneous pulse on what was happening. On a meta level, there was a lot of really good documentation about how to deal with all of this infra. Googlers maintained an incredibly comprehensive glossary, which made it easy for newcomers to figure out how to parse a sentence like 'I fed Starburst and ICA into RedAnt for Ansible'. There were also a ton of self-made guides that linked to other important documents or video presentations. There was some onboarding cost, but all together the communication infrastructure was simultaneously distributed, comprehensive, and functional.

I think communication at Google was still hard, but not nearly as bad as it could have been for a company that size. Even though I regularly worked with O(100s) of people from Mountainview, NYC, Zurich, and India I rarely felt like people were missing information and context. It's only now that I realize how impressive this feat was.